From Mercury to Modern LEDs

If you’ve worked in fluorescence microscopy for any length of time, there’s a good chance a mercury or metal-halide lamp has been part of your scientific journey. Before we talk about the upcoming February 2027 phase-out, it’s worth acknowledging something that often gets forgotten in the rush to “upgrade”. While these kinds of lamps are outdated and soon to be resigned to the history books, they’re also a huge part of the history of fluorescence microscopy itself.

Let’s take a quick look back at where they came from, what they made possible, and why the field is about to enter a new chapter.

A short history of mercury lamps in fluorescence microscopy

Mercury arc lamps trace their origins to the early 1900s, when they were developed as high-intensity, broad-spectrum light sources long before fluorescence microscopy existed in anything like its modern form. But by the mid-20th century, especially through the 1950s and 1960s, researchers realised that mercury lamps offered something crucial:

Bright, intense emission at key ultraviolet and visible wavelengths

Those sharp emission peaks lined up beautifully with the excitation requirements of early fluorophores. Suddenly, cell structures that had been difficult to visualise were lit up clearly and reliably. The technique rapidly spread into biology, pathology, microbiology, and medical research.

In other words: mercury lamps didn’t just support fluorescence microscopy – they actually helped enable it in the first place.

They were the backbone of:

-

early immunofluorescence

-

chromosome staining

-

microbial and parasitology imaging

-

the first fluorescence-based cancer diagnostics

-

early neuroscience tracer studies

Many foundational discoveries were made under a mercury lamp.

Then came metal-halide: stability meets convenience

By the 1990s and early 2000s, metal-halide lamps emerged as a practical alternative. They still produced broad, intense excitation light, but with:

-

better overall stability,

-

improved lifetime compared to mercury, and

-

less violent “end of life” behaviour.

They became popular in live-cell imaging because they delivered more stable illumination and required less frequent replacement. Many university teaching labs still depend on metal-halide systems today because they’re familiar, bright, and work well with traditional fluorophore sets.

So why are mercury bulbs being phased out in 2027?

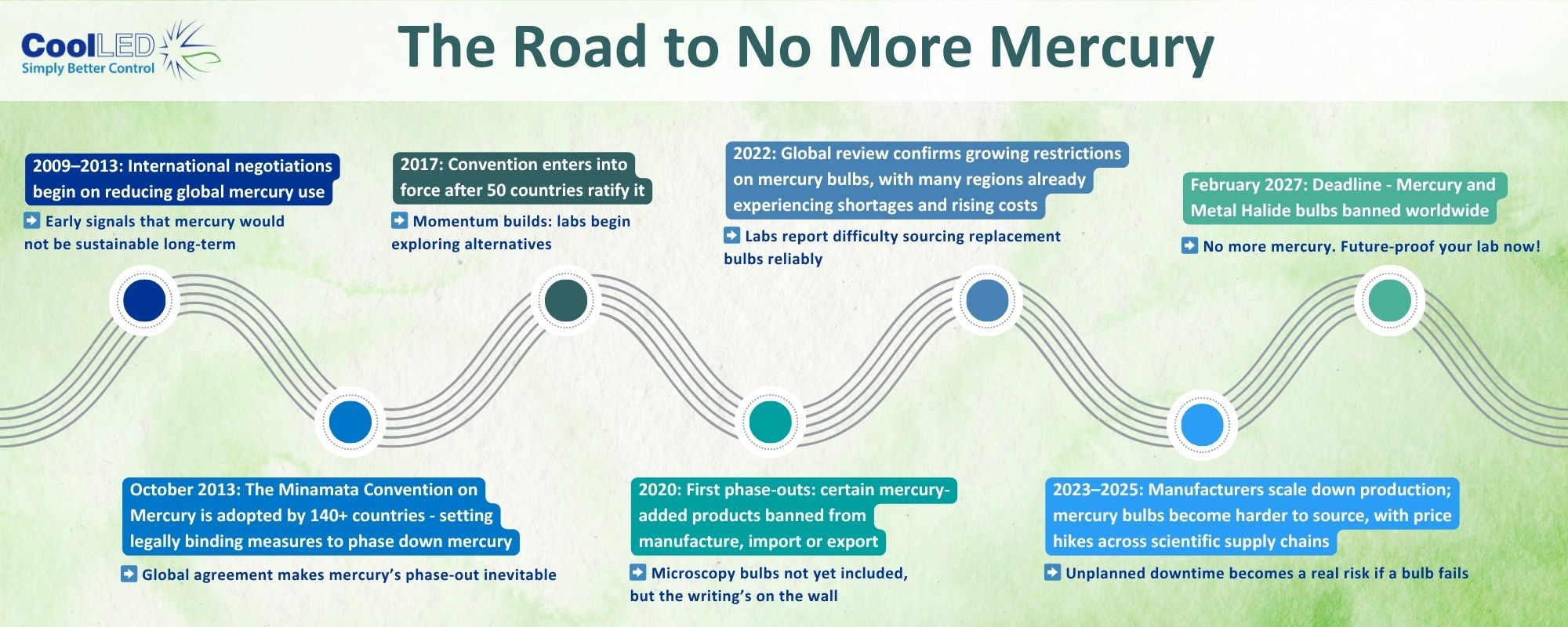

The February 2027 deadline is part of international environmental and public-health legislation targeting mercury-containing products. Mercury is hazardous to manufacture, transport, operate and dispose of, so the regulation isn’t aimed at microscopy specifically, it’s part of a much broader global initiative.

It doesn’t mean mercury lamps “failed” or are somehow obsolete.

It simply means the world is moving away from mercury as a material.

This gives labs two realities to prepare for:

-

Mercury and many metal-halide lamps will become unavailable.

-

Replacement parts, servicing and safe disposal will become increasingly difficult.

Which is why the next step is not about pressure to “upgrade”, but about making sure laboratories stay functional and compliant in the long term.

LEDs have matured into a reliable, high-performance light source

They offer:

-

consistent, drift-free intensity

-

defined narrow wavelengths

-

long lifetimes without bulb changes

-

instant on/off control

-

cool running with minimal sample heating

But most importantly, they allow labs to continue doing the fluorescence imaging that mercury lamps helped establish, without the regulatory and safety challenges attached to mercury-based light sources. It’s a continuation of the story, not the erasure of the earlier chapters.

A time of transition and a moment of appreciation

As we approach the 2027 phase-out, this isn’t just a logistical change for microscopy. It’s the end of a remarkably long era.

Mercury and metal-halide lamps lit up some of the most influential images in biology. They drove decades of discovery, shaped how we design microscopes, and supported entire fields of research.

The science many labs do today – from immunology to developmental biology to live-cell imaging – was built on the illumination these lamps provided.

LEDs now let us take the next steps with safer, more stable, and more sustainable technology. But it’s only fair to give credit where it’s due:

Mercury and metal-halide bulbs got fluorescence microscopy this far. LEDs will take it the rest of the way.

Written by Ben Furness / [email protected] / LinkedIn Profile